- The Role of Intelligence

- Learning Problems – Delay, Difficulty, Disability and Difference

- Causes of Learning Disability

- Specific Learning Disability

- Dyslexia – A Specific Disorder of Learning

- Diagnosis of Dyslexia – The Criteria and Models

- Phonology and Orthography – A Simple Explanation

- Who to See

- What Does the Future Hold?

The Role of Intelligence

Intelligence is a measure of a person’s ability to understand and learn, particularly in a school environment. It is not a single property. Measures of intelligence look at many factors involved in learning, such as language, memory, ability with visual puzzles, thinking speed, reasoning, logic and other thinking processes.

Results from intelligence tests are generally able to predict how well a child should be able to learn at school. However, they are not always correct as many other factors are also important. One of these is the presence of learning problems.

Learning Problems – Delay, Difficulty,

Disability and Difference

The terms Delay, Difficulty, Disability and Difference are frequently interchanged by professionals and lay persons alike when discussing learning problems and learning weaknesses in general. In some contexts such as open and casual discussion that is not meant to be diagnostic or prognostic in nature, this may be appropriate. However, too often these terms appear in formal reports and other types of formal communication with scant regard to their discrete meaning. This is a short note to present one possible way of understanding these regularly used terms.

Delay

The term delay implies that the child’s leaning problems will correct given suitable time. Thus their difficulties may be more linked with maturational tempo rather than neurological factors. There is probably not much to be gained by structured attempts at remediation or accommodation. In other words the problem can be left relatively untreated and given a reasonable period of time the child will recover naturally if suitable teaching takes place. However a short period of intervention could work quite well.

Difficulty

The term difficulty could be used to describe a learning problem that may present similarly to a delay but will not improve or only improve marginally over time. It usually means that the child has a problem in specific area of the curriculum. With additional regular tuition in the areas of concern the problem will likely correct.

Disability (LD)

The term disability is used to define a neurological and constitutional based disorder. Learning disabilities have a neurological signature and usually (but not always) represent a lifelong condition. This means that the child may have significant and long term academic and scholastic problems. Dyslexia and its various subtypes are examples of such disabilities. This type of problem has nothing to do with intellect, environment, social status, educational opportunity, self esteem or motivation. It can only be managed and improved with highly structured, direct, explicit and goal driven interventions that usually contain some elements of perceptual and processing training as well as multi-sensory literacy instruction.

Difference

This term, though in its infancy in terms of professional use, is being widely used by parents, support groups and learning advocates in an attempt to de-stigmatise Dyslexia and other learning ‘problems’. By using the word ‘difference’ it highlights the fact that though certain children find text based learning more difficult they find other activities and skills easy to learn and in fact may have above average abilities in other areas.

Some are concerned that the term “learning disability” focuses on an individual’s weaknesses and isolates them from other learners while the term “learning differences” highlights the fact that they simply learn differently than others do.

What exactly is the difference between ‘Learning Disability’ and ‘Learning Differences’ and why does it matter what terminology is used?

Individuals with learning disabilities do learn differently and have as much to offer and contribute as individuals without learning disabilities. However, presently the term ‘Differences’ has no formal or legal status and whilst the term Learning Disability is still not well understood it does at least attract legislative based support under certain disability laws and policies of Education Queensland. Unfortunately there is no such legislation connected with the use of the term ‘Differences’.

Literacy Care understands and supports the use of the term ‘Differences’ in a general way but officially endorses the use of the term ‘learning disabilities’ to ensure that individuals are appropriately identified and correctly managed. It is important to call a house fire a ‘house fire’ if you want house fire help.

The hope is that as time progresses Queensland and Australia will develop the sophisticated legislation that is needed to identify and effectively manage children who learn differently so as they have the same opportunities as their peers to develop and grow and have equal access to employment and all of life’s opportunities.

Causes of Learning Disability

The causes of LD is an area of rapid growth in research and understanding. A great deal is known, for example, about the cause of Dyslexia.

In most cases the cause is neurodevelopmental. This means that there is something different about the child’s brain, something that inhibits that area of learning. Often there is a family history of the same problem, suggesting a genetic cause.

Usually these problems are permanent although research into the phenomenon of brain plasticity suggests that specific types of intervention will positively impact on the physiological make up of the condition.

Even though children can learn, the rate of learning is usually slower than other children. This can cause problems throughout the child’s school journey.

Specific Learning Disability

Children with SLD have the intelligence to learn, but for some reason they are unable to learn at the expected level.

Specific learning disabilities refer to situations where the learning problem is limited to one area of learning. Usually these have specific names, for example:

- Dyslexia – when there is an LD that interferes with learning to read, spell and develop fluency in written text

- Dyscalculia – when the LD interferes with ability to learn mathematics

- Motor Dysgraphia – a disorder of motor coordination, interfering with a child’s ability to learn to write

Cognitive Dysgraphia – when the problem is with the production of written communication - Non-verbal LD – a complex learning disorder that affects cognitive functions where language is not involved.

- Language Learning Disorder – where underlying problems with language comprehension and production interfere with the language component of learning

Dyslexia – A Specific Disorder of Learning

In simple terms Dyslexia refers to the situation where a child has the intelligence to learn, but is not able to learn to read and spell as expected.

Dyslexia is not a new problem. The term comes from the Greek for ‘reading difficulty’. Over 100 years ago in 1896, the British doctor, W.P.Morgan, published in the medical journal ‘Lancet’, the case of a 14 year old boy who was bright, well adjusted, sociable, had no visual disturbances, yet was unable to learn to read despite the best of instruction. He knew back then that adults who suffered brain damage in a particular area of the brain (where visual information meets language) could specifically lose the ability to read. In his article, Dr Morgan proposed that this boy had a form of congenital (i.e., present from birth) Dyslexia. We have come a long way since that time in our understanding of Dyslexia, yet many myths remain. This information outlines what we currently know of Dyslexia, and sets the stage for planning a management program for children who have this disorder.

The phenomenon of Dyslexia is somewhat of an enigma. More commonly the child is male. They are usually intelligent, sociable and have reasonable language skills. In fact it is common to find a range of outstanding strengths in individuals who have Dyslexia. Yet for reasons that are essentially constitutional and neurological in nature they have a significant struggle in learning to read.

What Causes Dyslexia?

Hereditary

In most cases a child with Dyslexia will have one or two parents who also have Dyslexia. In some cases there are also grandparents and uncles and aunts with similar problems. In other words they inherit the genetics responsible for the problem from their parents.

Genetic

‘Genetic’ in this case refers specifically to instances where the affected child does have a close relative with Dyslexia. This means that the problem probably arose due to a mutation(s) in the child’s own genetic make-up which has affected how that child’s brain was ‘built’ during foetal development.

Acquired

Acquired difficulties referred to external factors such as accident, illness or injury that causes brain damage to the area of the brain responsible for reading. These causes are very uncommon.

In most cases…….

In most other cases we just don’t know – the medical tests all come back normal. But even in these cases we presume there is something different about the child’s brain.

Much of the research has looked in detail at the neurological causes of Dyslexia. One common finding relates to the question of Timing. Specifically, with either visual, auditory (or both) information coming in through the eyes or ears, timing issues of discriminating one piece of information from the next may be faulty. A detailed discussion of this research is beyond the scope of this website.

The ‘take home message’ from all this research is that the brains of Dyslexic individuals are different. Specific brain functions do not work as well as they should, and the end result is that the child struggles to learn reading and spelling to a degree far greater than people expect.

Diagnosis of Dyslexia – The Criteria and Models

Specific Learning Disability or Dyslexia essentially exists in two broad spheres:

Unexpectedness

The first sphere is defined by the notion of “unexpectedness” and is usually concluded on the basis of exclusionary criteria. This means that it should be reasonably clear to the diagnostician that it is a case of significant and unexpectedly slow academic progress. This failure to thrive academically should exist despite adequate instruction over a number of years by qualified professionals using acceptable methods. It also should exist despite normal biological and social development, average socio-economic status and a normal home life. The difficulties with written language should exist in the presence of at least average intellect and average language function including vocabulary and speech production. Furthermore, these problems usually persist despite the continued development of certain strengths. Thus the principle of “unexpectedness” is clearly visible.

Constellation Disorder

The second sphere of diagnosis is defined within the idea of constellation disorder or multi-pattern disability. This means that the child experiences difficulties within a range of developmental areas and it is difficult to ascertain whether or not the learning problem is a primary pathology or a secondary condition spawned from the primary pathologies. In this sphere of diagnosis the learning problem is generally expected and probably related to the other coexisting conditions.

As with all developmental problems, the diagnosis of Dyslexia does not come from a blood test or battery of psychological or educational tests. There is no one test or set of tests for Dyslexia. The diagnosis therefore is essentially clinical and is made if a child meets a series of criteria.

Criteria – Not all may be needed to make an accurate diagnosis

1: The Unusual Phenomenon

For dyslexia the unusual phenomenon is clearly an inability to learn to read at the same rate as would be expected for a child of that age and general ability.

This is made complicated by the fact that children only start to learn to read around prep or the first grade of school. As a result, it takes some time before the child’s problem becomes clear. However there are now early screening devices that can predict with some certainty whether or not a child is going to learn to read at the expected rate.

Other children have had to move ahead in their reading, leaving the dyslexic child behind. For education services, often the arbitrary decision is made that a child has to be at least two years behind in their reading skills. For this reason, the diagnosis of dyslexia is not often made before the third grade.

2: No Alternative Explanation

The most common alternative explanations are:

- Intellectual: The child may have a global intellectual disability which affects all academic work, not just reading

- Learning Opportunity: The child may not have had the opportunity to learn to read.

- Attention: The child’s attention and concentration may have been so poor they have not been able to learn to read

- Anxiety: Children who are naturally highly anxious, abused, or in households of domestic violence may be so anxious and distracted that they cannot concentrate and learn

- Visual: Children must be able to see the written letters and words

- Language: Children must have sufficient language skills to understand the words and sentences

To make the diagnosis of dyslexia, each of these possible alternative reasons for the reading problem should be excluded.

3: A Consistent Story

Children with Dyslexia struggle with reading from the very start of the process. They may have had delays in their language development, but not necessarily.

In many (if not most) cases there is a family history of reading difficulty which is not often recognised (the key is adults that still have spelling problems, and choose not to read if they can avoid it).

Putting These All Together

When diagnosing Dyslexia we work through these criteria. If the child has poor reading, spelling and fluency skills but is otherwise intelligent and has no wider coexisting conditions that have stalled learning and the story is ‘consistent’ then the clinician has strong cause to apply the following three models in an attempt to be definitive in diagnosing Specific Learning Disability or Dyslexia

Diagnostic Models

1: The Strengths Model

As mentioned earlier children (and adults) with Dyslexia usually have an array of above average abilities. Commonly they excel at music, art, drawing, drama and sport. However people with Dyslexia can often be good at maths, computing and even story telling. The diagnostician must assess a child’s strengths as much as their weaknesses in order to correctly diagnose Dyslexia

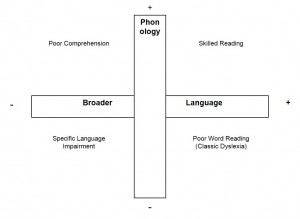

2: The Phonological and Orthographic Processing Model

This model is designed to elucidate the child’s capabilities relative to processing phonological (sound) and orthographic (symbol and pattern) knowledge. The three composite areas of phonological processing are: Phonological Awareness, Phonological Memory and Automatic Rapid Naming. These must all be thoroughly assessed. The resulting profile can be compared to the child’s reading ability, intellect and general scholastic performances. Such information also serves as a prediction of what recovery work will be needed and how severe their difficulties are. Orthographic processing has 4 composite areas and is measured more qualitatively. Orthographic processing refers to how a child understands the visual symbol and pattern side of written text

3: The Intelligence to Performance Discrepancy Model

This model attempts to demonstrate that there is both a clinically and statistically significant disparity between the child’s intellect and their academic (in particular reading) ability. Past judgments have considered a two year disparity as being significant or severe. This model should not be used in isolation.

4: The Reading Language Model

This model implies that the affected child has average to above average language abilities but they read poorly and have poor phonological processing but good comprehension.

Phonology and Orthography – A Simple Explanation

Phonology – The Sounds in Words

People who have learned to read normally are able to hear all the sounds in words. Their brains can dissect out each of these sounds individually. This process begins even before birth – from the first time babies hear language their brains ‘chop up’ the words into the component sounds and store the words as combinations of te sounds.

To understand this try saying a few words to yourself – TRUCK, GRAIN, FROG, BUTTERFLY….As you say them, notice how your brain is able to ‘hear’ and identify each of the important sounds that make up these words.

These sounds map onto individual letters, or groups of letters (such as ‘ch’). When you learn to read, you learn to associate the sounds with the letters. Specifically, coming across a new word, each letter or letter combination has a corresponding sound. When you ‘sound out’ the new word, your brain recognises the sequence of sounds and identifies what word the sequence of symbols on paper refers to.

Disordered Phonological Awareness

The most common cause of Dyslexia is disordered phonological awareness.

What this means is that the Dyslexic individual’s brain cannot identify the component sounds in words at a sufficient level of detail. Just as you can recognise tunes when the music you are listening to is fuzzy, Dyslexic individuals can discriminate enough to identify the spoken words. However, they cannot individually identify each component sound well enough to store the words in their brains as the full, exact sequence of sounds.

When they then come to reading, the process of identifying sounds from the written symbols, blending these together into a word and recognising that word from the sounds falls apart. This is because the word they ‘put together’ from the letters on paper is different from the word as stored in their brain.

The Visual Side of Reading (Orthography)

There is a long history of trying to understand Dyslexia as a visual problem. As early as 1917, a British Ophthalmologist, James Hinshelwood published a paper on ‘congenital word blindness’. He noted that the eyes of these children could see normally (there was no optical error). He also noted that the eyes could move and track normally. In the 1920s Samuel Orton, an American Neurologist felt that Dyslexia was due to a defect of visual recognition – children struggled to see letters in the correct orientation and sequence. He used the term, ‘strephosymbolia’ which means twisted symbols.

Many researchers have looked at this area since that time. The combined evidence from this research seems to be:

- Dyslexia is not caused by problems with the eyes. This means that eye exercises will not make a substantial improvement in reading ability.

- Some children have problems with visual perception and visual memory. This is what the brain does with information that comes in through the eyes.

- If children have problems in this area it can affect them in three broad ways.

The first is letter recognition. Letters that are similar (such as b and d, or p and q or u, n m, or w) may be difficult to distinguish from each other.

The second is word visual memory also known as Eidetic Imagery. As we automate the process of learning to read, we increasingly use our ‘sight vocabulary’. We recognise words from their shape rather than the sounds of the letters. This is like recognising a Chinese character. Children with visual sequential memory problems struggle to automate their recognition of words, so that even words they have seen many times are viewed with as seen for the first time.

A third problem is spelling. Because visual recognition of words is poor, children write words as they sound, but cannot ‘see’ that the word is spelt incorrectly because of their visual perception and memory difficulties.

A more complex definition of orthography is available elsewhere on the website.

Language

Another area where children can struggle is with language. One strategy children use when reading and interpreting new words is to use the context. This means that they know what the passage and sentence are about, and can intelligently predict the word. We may use the first letter or two, the length of the word, the meaning of the other words in the sentence, pictures and any other clues in this process. (Although mature readers do not usually use this method).

When a child’s (immature reader) language skills are generally weak, they struggle to use their language in context to make these intelligent predictions. This is then another reading strategy they cannot use.

Putting it All Together

There are some children for whom several or all parts of reading (the visual recognition, visual memory, phonological understanding and language more generally) may be only a little weak. They then struggle to put all these steps together as they are learning to read. Sometimes they also have problems with attention, concentration or working memory further limiting their ability to assemble the set of skills required. This is probably a more temporary cause of reading problems as once these children finally ‘get it’, they often learn to read fairly quickly from that point on.

For children with Dyslexia one or several of these processes may be severely problematic. As indicated above, the most common cause is Phonological Processing but each child is different.

Additionally, a child’s vision and hearing should be screened to exclude sensory difficulties.

Who to See

Dyslexia is a condition that crosses the boundaries of both psychology and special education. Thus the best person to diagnose Dyslexia is a neuropsychologist or special educationalist. An experienced special educationalist who has neuropsychological information about the child is in a position to make a sound diagnostic statement about the child’s learning. The benefit that a reading specialist has over a psychologist is that they are often better trained and qualified to manage the post assessment period when a treatment intervention is in place.

What Does the Future Hold?

From a medical perspective, the ‘problem’ in the brain of a Dyslexic individual may persist for life. It does not necessarily get worse, but it is not a temporary immaturity, where the brain is slow to develop. It is a neurological difference which they do not grow out of.

This does not mean, however, that Dyslexic individuals cannot ever learn to read, write and spell. What it does mean is that their rate of development in these areas will be slower than children of the same age without Dyslexia.

As a result:

- Dyslexic children are able to learn to read at their own, slower rate. As long as their motivation and effort persists, even the most severe Dyslexic should eventually be able to learn reading to a level that allows independent life and vocation.

- Dyslexic children seldom ‘catch up’ to the other children in their grade. They are always slower with their literacy skills, and the gap between what they can do, compared to the rest of the grade, often widens rather than narrows over time.

Secondary Problems

Imagine you are a smart child, struggling to read in a classroom where the other children could read well. Perhaps you are asked to read in front of the class and humiliated. Perhaps you are given maths problems in writing which you fail at because of your reading, even though you are good at maths.

This creates for you a dilemma. You have to work out why it is you are different. Perhaps you are told you are lazy, immature or have a bad attitude. You may conclude that you are stupid:

Whatever you conclude about yourself, you have to handle your situation.

- If you are an ‘outward’ child, you may start to fidget, be the class clown, or use other behaviours to avoid reading. This could turn into more serious behaviour problems

- If you are an ‘inward’ child you may retreat into your shell, withdraw from the classroom activities and school more generally. This could turn into mental health problems such as depression

- Either way, you will probably begin to hate reading and actively avoid it. Then your rate of learning to read may stop altogether, you fall further behind, and the problem worsens

Secondary problems are those caused by how a child adapts to their situation. They are potentially reversible if the underlying dilemma is understood and managed well.

Tertiary Problems

When a secondary problem (behaviour, depression) has been present for some time, it can become firmly established. This can lead to a child disliking themselves, and making choices in adolescence and adult life which are harmful. Most parents are instinctively aware of this and fearful of a child dropping out of school, being unemployable, having depression, drug or alcohol problems, being lonely, angry or sad or even self harming.

Whilst these problem make Dyslexia and learning disabilities sound bleak, there is a great deal that can be done.

The primary problem can be greatly improved, whilst the secondary and tertiary problems can be prevented.